2025: It was the best and worst of times

For last year’s end of year reflection blog post, I shared the lyrics of John Lennon’s Imagine, and its messages feel even more urgent this year. I won’t dwell on the grim state of the world with the rise of authoritarianism and the unthinkable harm caused by a small number of men waging brutal wars and other despicable acts. I do want to share a conceptual framework that helps me understand what’s happening in the world right now and my personal motivation to do everything I can to make a better world and to inspire others to do the same.

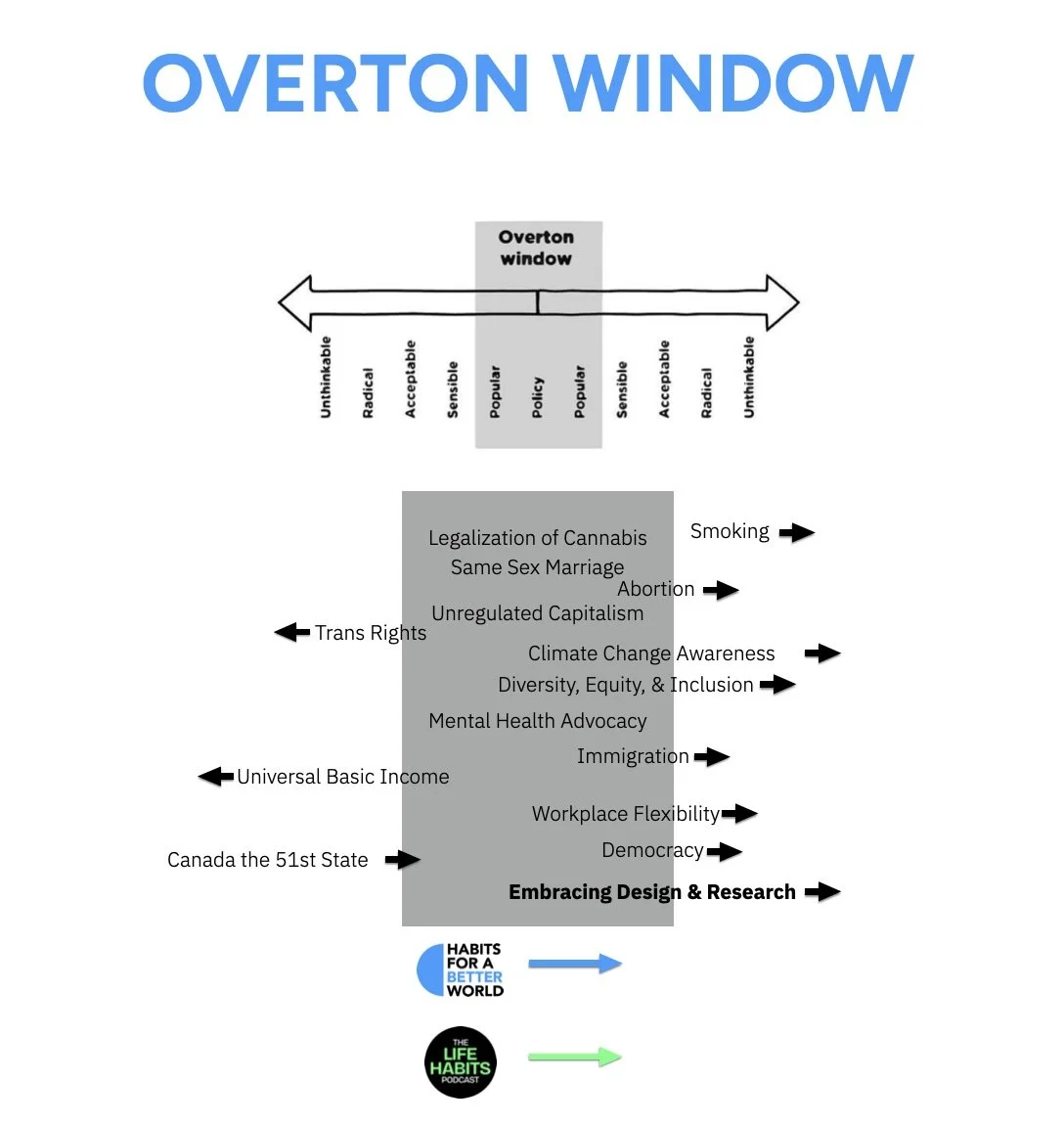

overton Window

That conceptual framework that I learned this year that provides a understanding of what’s happening in the world is called the Overton Window.

The Overton Window describes the range of ideas and policies that are considered acceptable or normal in public discussion at any given time. Ideas inside the window feel reasonable and mainstream; ideas outside it are seen as extreme, unthinkable, or taboo.

The window isn’t fixed. It shifts gradually or suddenly. Understanding the Overton Window helps explain how societies change, not just for the better, but also in troubling backward directions.

When people say, “someone should do something about that”, I say, “why not me or us”.

I’m so pleased this year that members of Carly and my Habits for a Better World nonprofit have finished laying the technical and logistical foundation for us to have major impact on several world-changing initiatives that will move those initiatives into the Overton Window. I’m also delighted that Mandy Kloppers, MJ Shaar, and Suzanne Joy Clark have joined me a regular co-hosts on my reimagined Life Habits Podcast, now also in video on YouTube, examining evidence-based habits to improve personal life habits that will also have a positive impact on the world.

MAJOR MILESTONES

70 Years on this Earth

I’ve entered my seventies this year. I’ve never celebrated a birthday quite like this one previously and, wow, did my family and friends ever help make it an amazing event.

My brother Harrie, son Elliot, long-time friends Bob and Rick, teaching colleague Michael, and co-founder Carly gave wonderfully heartfelt speeches.

The entire evening was organized by my amazing daughter, Emma, with help from other family members. We rented out Dark Horse Espresso Bar for the night, with catering from the phenomenal plant-based restaurant, Animal Liberation Kitchen. To help guests from different parts of my life connect, Emma worked with me to create a “𝗪𝗵𝗼 𝗞𝗻𝗼𝘄𝘀 𝗞𝗮𝗿𝗲𝗹 𝗕𝗲𝘀𝘁?” quiz with True or False and write-in questions. To find the answers, people had to talk to others they’d just met—and it worked beautifully. Many said it wasn’t just fun—it was a fantastic way to break the ice and get to know each other. I highly recommend it if you’re planning a similar event. We also played a traditional Dutch game of Sjoelen (shuffleboard), which turned out to be an unexpected hit.

10 YEARS OF TEACHING

I also celebrated a full decade of teaching as an Industry Professor in the McMaster University DeGroote Schools of Business and Medicine.

I developed course material for and taught several programs including the Executive MBA in Digital Transformation program for rising star business leaders, the Emerging Health Leaders program for pre-med, medical students, and early career physicians, the Innovation by Design program for pan-university undergraduate and graduate students from any faculty, the Directors College for members of boards of directors, the Collaborative Health Leadership Governance program for board directors of health organizations, and the National Health Leaders program for top health leaders in Canada.

FIRST YEAR OF SERVING AS A BOARD ADVISOR

I’ve previously been on boards of directors for IBM’s Employee Charitable Fund, the VegTO nonprofit, and I currently serve as the President of the Habits for a Better World nonprofit.

This year I began serving as an advisor to the Food for Climate League nonprofit, a coalition of individuals passionate about democratizing sustainable food culture through innovative, human-centered communications. and also the PRAXXI for profit startup, an AI-powered platform that helps organizations and leaders build adaptive and resilient teams, enhance key capabilities, while empowering individuals to design their careers and lives in a world shaped by AI and constant change.

Both of these organizations are trying to improve the world and I feel fortunate that they trust me to advise their staff in the case of FCL and the leadership team in the case of PRAXXI.

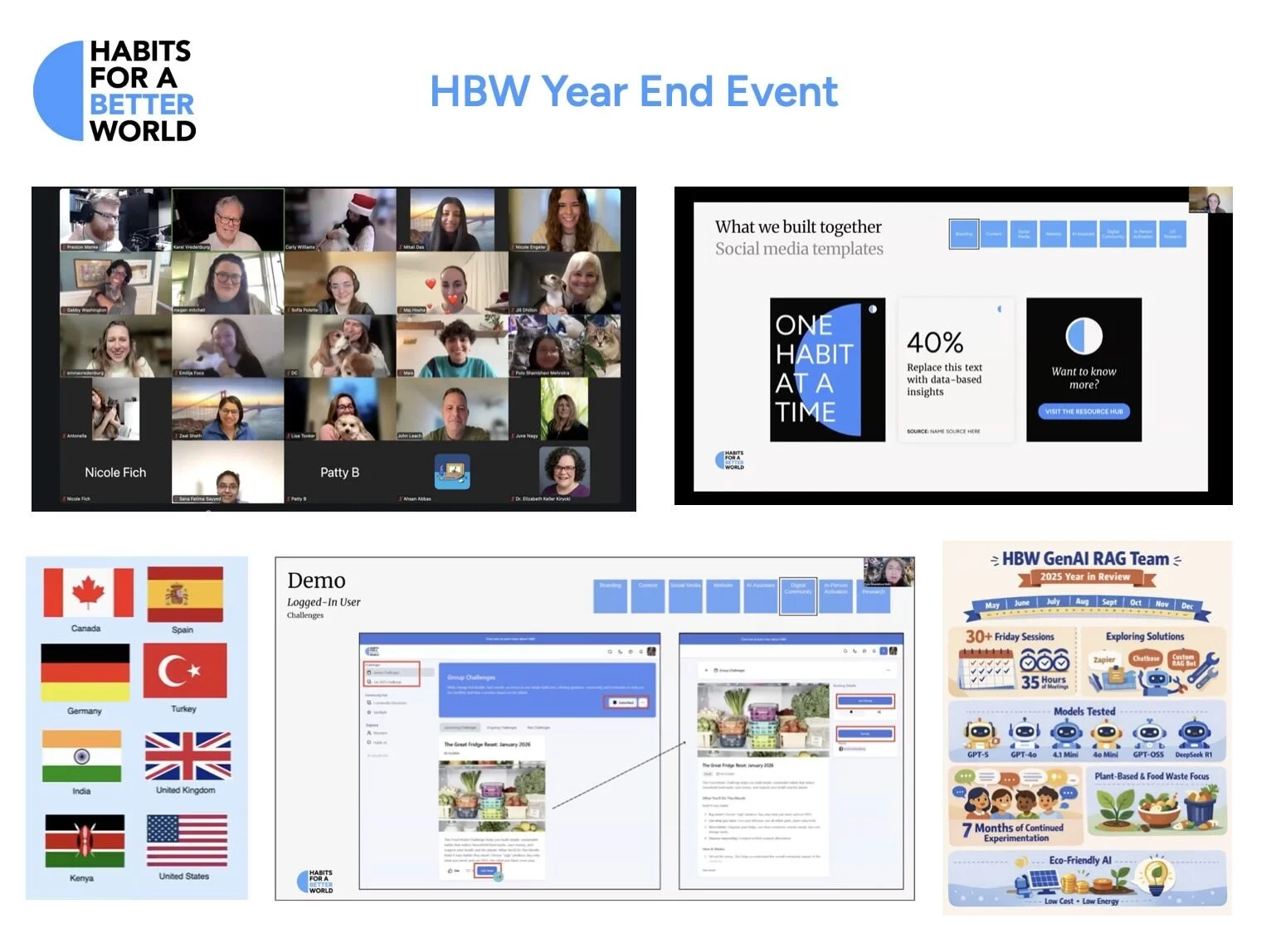

BUILT THE FOUNDATION OF HABITS FOR A BETTER WORLD

I’m so pleased with what Carly and my Habits for a Better World teams accomplished this year and the incredible quality of the work. I’m also so heartened by the heartfelt reflections team members recently shared about what being part of this organizations has meant to them and how the experience has improved their lives in a variety of ways. I love working with this group of diverse highly talented friends from all around the world with a passion to use their skills to create a better world together.

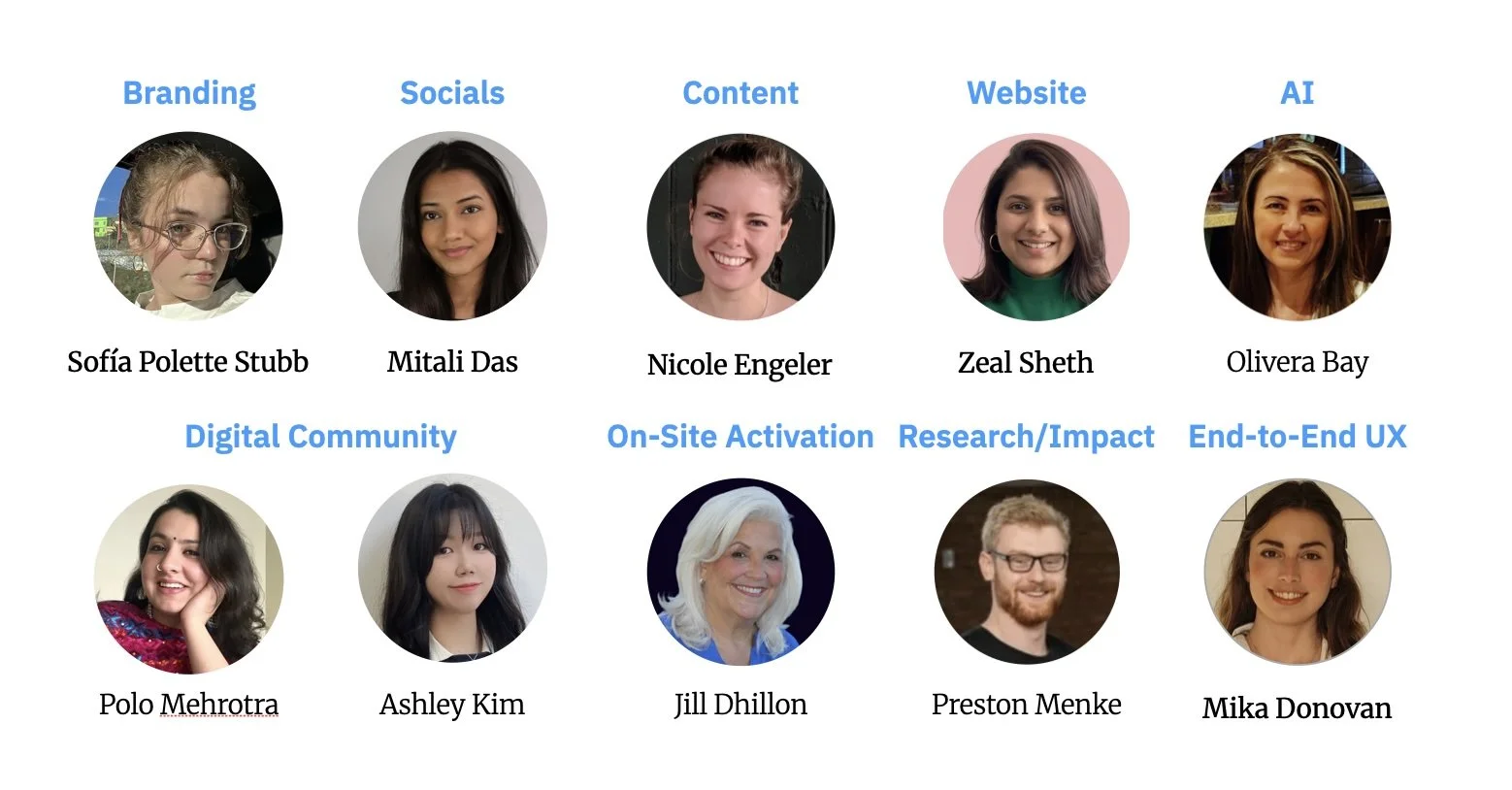

I’m so proud of each of the members of what we call our foundation teams and also of the leaders of those teams which include the following:

Branding—Sofía J. Polette Stubb

Content—Dr. Nicole Engeler

Social Media—Mitali Das

Website—Zeal Sheth

AI Assistant—Olivera Bay

Digital Community—Shambhavi Mehrotra (Polo) & Ashley Kim

On-Site Activation—Jill Dhillon

End-to-End Experience—Mika O'Donovan

Research/Impact—Preston Menke

And of course, I’m forever thankful for my wonderful co-founder and friend, Carly Williams.

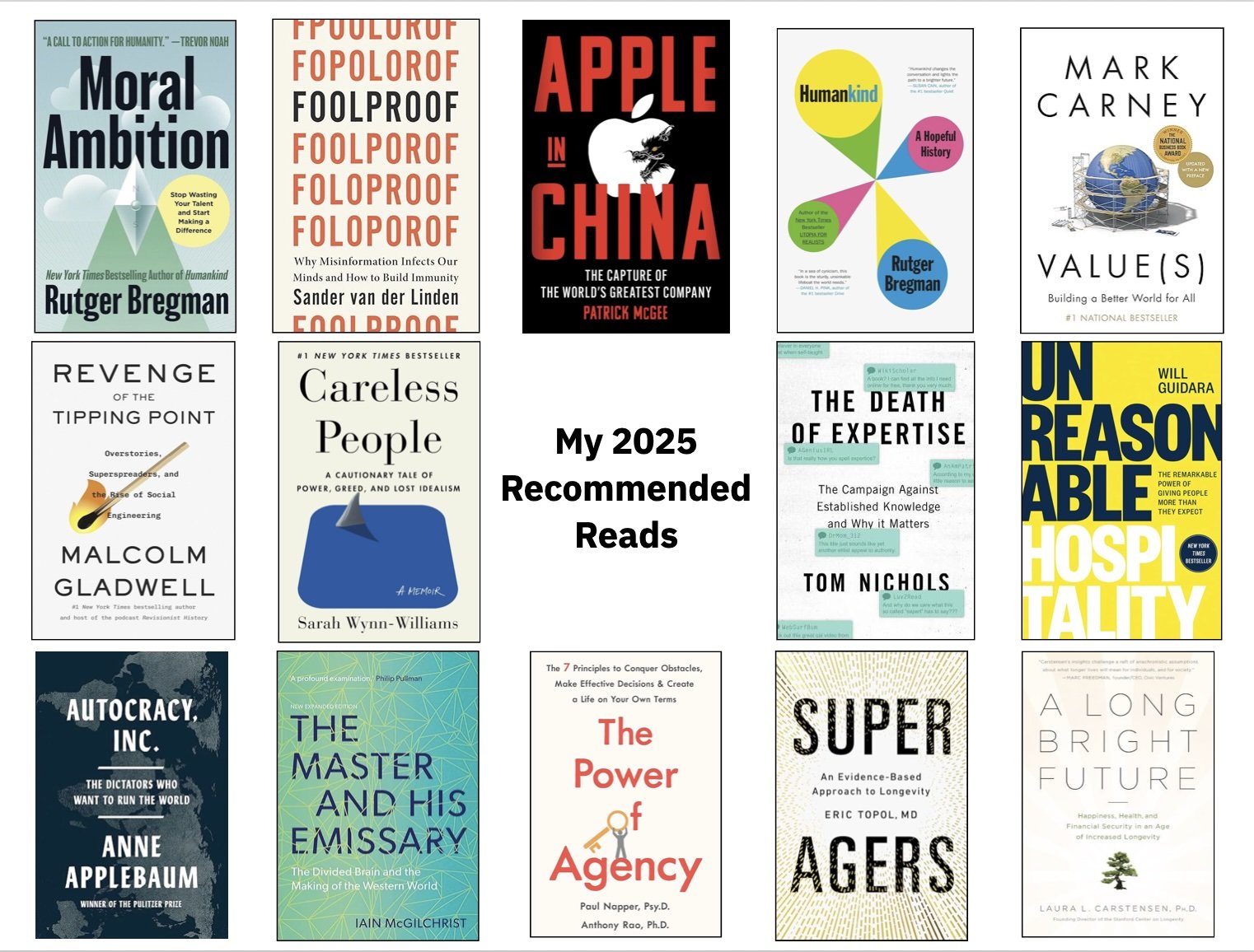

THE BOOKS I READ THIS YEAR THAT I RECOMMEND

Lastly, I’d like share some of the books that I read this year in case you haven’t read some of them but would like to. Some of them I thought I should read, a couple I re-read, and yet others, I just read out of sheer interest. I thank the authors and especially those who were kind enough to be on my podcast.

I hope to share at this time next year the second book I’m currently writing, and maybe even a third too in collaboration with some friends.

Career Advice I Give My Clients

Javier Andrēs Bargas-Avila tagged me in a recent LinkedIn post sharing the disturbing news that “hundreds of UXers at Google were laid off this week”. He mentioned the interview I did with him on my Life Habits Podcast discussing the topic of “Dealing with Job Loss”. Javier regularly posts about large job losses like that at Google where he used to work and he also provides support and coaching for his former colleagues.

I posted a similar sentiment when I heard about a layoff at IBM where I used to work. Many former staff members, colleagues, and even other IBMers I didn’t even know but who knew of me followed up for individual coaching sessions.

Javier and I share a deep empathy for people dealing with job loss and we have a shared passion to help.

Previous insights and advice

I’ve reflected on this broader topic in previous blog posts such as the one on Don’t Layoff Employees or Impose Tariffs: Make Better Products examining the root causes, Applying for a Job: An Employers Perspective giving some advice in my role at the time serving as the Global Vice President of UX Research at IBM, and Designing Your Career for the Future. You can also check out podcast episodes I’ve done on the topics like Landing the Job, Creating Your Own Job, Designing and Marketing the Product YOU, and Future Proofing Your Career.

Lots has changed in the last three years in the job market. I’ve also in that time converted my career coaching that I did during my more than three decades with IBM into a professional career and life coaching practice. I’ve been working with many people who have lost their jobs or were unhappy in their jobs and a unfulfilling life and looking for ways to improve their chances of getting another job and a more fulfilling life.

Why I’m sharing this with you

I realize that many people in those situations need a place to start and a paid coaching call isn’t the way they feel comfortable initially. I feel for each of you who are in this situation and empathize with you so I’d like to help by sharing in this blog post key items of advice that I give my coaching clients.

Here’s My advice

Early days

Take a breath and be kind to yourself

The news you’ve just received is shocking, often totally unexpected. As Javier also points out, realize that it isn’t your fault, typically it’s just that your number came up in a company that treats employees like numbers and your number needed to go. It’s often so inhumane. Getting this kind of news is like any other bad news you may get in life but often others around you won’t be as supportive. Typically, you need to deal with a whole new identity after often years of identifying with your job or role. That’s hard. Take a breath and be kind to yourself. Some of the people I’ve worked with who have decent severance packages take time off or even take a vacation rather than immediately starting their job search. I think that’s healthy and will put you into a better frame of mind when you start your job search.Celebrate your career progress

It’s rarely your own fault that you were let go, so don’t get down on yourself. Instead, sit back and reflect on your career whether it’s been a just a few years or often many years. Think about the successes you’ve had, the people you’ve met and worked with, and what you’ve learned. Feel good about what you’ve achieved.Take stock for your next steps

Before delving into a job search, consider what you want from a job and your life. It might seem strange for me to suggest that in such a tough job market but several of the people I’ve worked with who have worked for many years in the tech sector have decided to take a totally different direction sometimes with a cut in salary but a boost in life fulfillment by joining a nonprofit or even starting their own business.

Getting started

Use a designer’s/researcher’s mindset

When designers and researchers do their work to create a product or service, they use a well-known process and specialized craft to do so. They make sure they do research on the intended users, ensure that they make the design align with the users needs, minimize the time and effort it will take for a users to use the product or service, and so on. However, in my experience, when it comes to finding and getting a job, those same designers and researchers forget everything they know and take the perspective that they often criticize that developers take of giving the user whatever they think they need. While I do coach others, for designers and researchers I advise them to use their skills to design the best product and the most important product: they themselves.Your LinkedIn profile is your product ad

Consider your LinkedIn profile to be your product advertising. Make sure that it represents how you want to be represented, the photograph, your roles, the About section, all of it. Make sure that it is differentiating and what the jobs you’re looking for are asking for. The people I’ve worked with often have very generic descriptions About sections or providing way too much information. It’s an ad, treat it like one. What are the top three ways you’re different and more desirable as an employee than others and what type of role are you looking for.Your resume and portfolio should be the digital version of you

Again make sure to lean into your designer’s or researcher’s mindset to design the best digital product you’ve ever designed: the digital version of you. Consider that recruiters and hiring managers will be interviewing you in absentia by reading your resume and portfolio. And the interview will often be very brief, so keep the information you’re providing on point, differentiated, and focused. Make your resume beautiful but also realize that the words in it will also be read by a machine either solely in the early filtering process (often heavily used by larger companies) or together with humans. I often get into deeper evaluations of resumes and portfolios during coaching sessions but my general observations are that most people put too much detail into them. Remember, would you do that when designing a product? No, you’d empathize with the user, in this case the recruiter or hiring manager, and make it simpler to consume. If your portfolio lists similar work that you’ve done for several clients, don’t create a page for each of those, instead just create a single page showing a representative instance and just list the clients you’ve done that type of work for. Make sure to lean into vibe enhancing your resume and portfolio by using ChatGPT.

Applying

Finding the jobs you’d like to apply for

Think again about the item above about taking stock of what type of work you’d like to pursue next. If you’re in tech now, maybe you’d like to consider roles outside of tech. Be realistic about the jobs that you’re qualified for and double-check the job posting to ensure that you satisfy the key requirements. Many jobs will stipulate the city and country you’re required to live in and be in the office for a certain number of days. Don’t apply for those thinking that you can convince them to make it a remote job. The job market is too tough right now so you’ll be wasting your time and the recruiter’s time by applying in that way.

Interviewing

Congratulate yourself for getting an interview

Most applications don’t get you to an interview so feel good about what you’ve accomplished in the process thus far.Do your research

Consistent with my theme of using your designer’s/researcher’s mindset, explore more about the company, the recruiter, and the hiring manager, whatever you can find. When candidates I interviewed had checked me out on LinkedIn and also read some of what I had written, I was impressed that they were prepared and already had demonstrated their interest in the job, the company, and me. It also allowed them to ask particularly well-thought out and pertinent questions.Practice and rehearse for your interview

Some of the people I’ve worked with assume that they’ve been in work meetings before including one-on-one meetings so they should be able to just wing an interview. Job interviews are different, especially now. You need to practice and rehearse. Write down the kinds of questions you think you may be asked and then go and answer them. And don’t do it on your own. Recruit a partner, family member, friend, or even your dog to work with you on this. The advice I now often give is to turn to your very knowledgeable colleague, ChatGPT or your preferred GenAI assistant. Give it all the information your interviewer has been given and then prompt it with something like “you are recruiter for company X and you are going to interview me for this job” and give it the job posting. Even ask it to ask you tough questions about things that you’re concerned about regarding your resume or portfolio like gaps, potentially your age (good interviewers won’t ask you directly about age but may prod you about being too inexperienced or the obverse too experienced). If you have the paid version of ChatGPT, you can also have a full live verbal interview. If you don’t, you can print out the questions and have a friend ask them to you.Doing the actual interview

Make sure to arrive on time by planning to be slightly early, whether in-person or virtually. Take some deep breaths and try to remain relaxed. When asked a question, don’t rush to answer, think first and then respond. Ensure that you fully understand the question first and ask for clarification if you don’t. You don’t want to be answering the wrong question. Get back into your designer’s/researcher’s mindset and consider what the interviewer would like to know rather than simply blurting out everything you want to tell them about how great you are. In initial mock interviews I’ve done with clients, they often focus so much on what they want to say that they don’t actually answer the question. They often speak in generalities and don’t focus enough on what differentiates them from others.Waiting for the reply

Celebrate if and when you get a job offer. But in this job market, that isn’t often the case that you get an offer. Don’t despair. If you have the rare opportunity to learn why you weren’t offered the job from the company, reflect on that. More often though regrettably, you don’t get any or much in the way of feedback. So, reflect on how the interview went yourself and consider what you could improve upon.

Other things to consider

Self improvement

Your feedback from or your personal reflection on the interview if you didn’t get the job may lead you to consider further developing or honing your knowledge, skills, and/or experience. This could take the form of additional informal or formal education. One incredibly important area to focus on is Generative AI regarding typical more general use-cases but also ones directly related to your discipline. Realize that AI is also often now doing the work that entry level designers and researchers used to do so you should also focus on further developing your higher level skills as discussed in this article written by my designer son. If you need to get more experience, fill a gap in your employment, and/or want to feed your soul and not just your wallet, consider volunteering your skills with a nonprofit. I co-lead one where the other co-founder and I are committed to giving you work experiences that you desire to have. Check it out at Habits for a Better World.Consider fractional roles

For decades, careers followed a predictable path: one company, one role at a time. That model is changing. A fractional role is part-time but strategic. You’re not freelancing task-by-task. You step in as a leader or specialist for a set number of hours or projects. Smaller organizations can’t always afford full-time senior staff. Startups and nonprofits need expertise without the overhead. And, the staking stock reflection I mentioned earlier is leading professionals to want greater flexibility, variety, and alignment with their values. Fractional job postings grew by 57% between 2020 and 2022. Today, about one in four U.S. businesses already use fractional hires, and that share is projected to reach one in three in the coming years. It’s no longer a niche trend but becoming mainstream.

My own path

When I retired a year and a half ago, I decided to take on several factional roles: president and co-founder of a nonprofit, Industry Professor at a university, hosting my podcast, serving on a couple of boards of advisors for a startup and a scale up, taking on the occasional consulting gig, and offering my career coaching services. I couldn’t be happier.

Next steps

I hope that the advice I’ve provided in this post is helpful to you. Feel free to reach out in a LinkedIn DM if you have any questions, and if you want further one-one-one customized advice to your own situation consider my career coaching services or Javier’s as well. We’re both experienced executives in the tech field, have deep empathy for the many people who are unemployed or underemployed, and have honed our coaching to suit the times we’re living in.

I’d like to thank you for reading through all of this and I wish you well in your job search!

AI: A Prosthesis for the Brain

Almost four decades ago, I conducted research supported by the Medical Research Council to create a new model for improving user interfaces by going beyond what people said—beyond surveys and self-reports—and tapping into what their bodies revealed in real time. I used heart-rate monitors and galvanic skin response sensors to better directly understand emotional and cognitive states as users interacted with technology. I also used an electroencephalogram (EEG).

Twenty-five years ago, I wrote much of my first book not by pressing keys on a keyboard but simply voicing it while driving using IBM ViaVoice speech recognition system running on my laptop on the passenger seat.

Then thirteen years ago, I had the honor of forming and leading a research and design team that created the first commercial AI product—IBM Watson—initially used to diagnose and recommend treatments for cancers.

Now it feels like the these innovations have the potential of coming together to remove the user interface entirely as we know it initially with alternative external user interfaces but perhaps eventually with new brain prostheses with AI. I dreamed of the future potential of the technology back then and I’m doing that again now in this post.

Today, we find ourselves at a new inflection point. AI isn’t just assisting us, it’s beginning to replace many of the tasks that once defined human work. From diagnosing diseases to composing music to writing code, AI systems are outperforming us in areas.

So what does that mean for us not just as workers, but as humans? One path is withdrawal: resisting the tide, clinging to human-only capabilities. But another path, the one I’m increasingly drawn to, and levels of integration. Not just using AI to augment our memory, cognition, and communication in daily life, but exploring the profound implications of the possibility of physically integrating AI into our bodies and brains.

This post is a personal and philosophical exploration of that possibility:

What does it mean to evolve with AI? What might we gain—or lose—if we choose to directly wire intelligence into ourselves?

Phase One: Augmenting Ourselves with AI

Before we talk about wiring AI into our brains, we should acknowledge that, in some ways, we’re already partway there.

Every time we ask a language model to summarize a report, generate ideas, or translate our thoughts into fluent, structured communication, we are extending our cognitive capacity. Insightful AI futurist, Mo Gawdat, says that using AI is an automatic way to boost our IQ by about 100 points. I love that way of characterizing our use of AI.

These tools are powerful, not because they replace us, but because they amplify us. They give us faster recall, broader reach, and new creative fluency. We’ve gone from memorizing facts to retrieving them instantly. From thinking linearly to parallel thinking with systems that never sleep, never fatigue, and seem to learn faster than we ever could.

This is augmentation, not replacement.

And it’s already reshaping what it means to be capable, productive, and even emotionally attuned. We offload memory to external systems. We enhance our writing with stylistic suggestions. We run meetings with AI note-takers that summarize dialogue more efficiently than any human could. We have auditory conversations with them as an always available friendly companion to laugh at our jokes and support us when we’re feeling down (more on that in a new series for my Life Habits Podcast coming soon). These are not just tools—they’re cognitive scaffolds, and they’re becoming part of our mental and social operating system.

But augmentation through devices—screens, keyboards, voice commands—still keeps the AI outside of us. It’s a conversation, a partnership. We’re still the ones initiating the prompts.

The question now is: what happens when that interface disappears altogether?

Phase Two: Integrating AI DIRECTLY IN the Brain

In a widely discussed scenario titled AI 2027, a group of respected thinkers laid out a month-by-month projection of how artificial intelligence might cross the threshold into superhuman capability within just two years. According to their timeline, AI could soon outperform the best human programmers, then rapidly outpace human researchers, and eventually enter a recursive loop—where it designs increasingly powerful versions of itself at speeds no mere human mind can follow. If that trajectory proves even partially accurate, the only viable way to keep pace may not be to compete with AI, but to interface with it.

Rather than standing outside of AI systems—trying to regulate, interpret, or resist them—we could instead design them as cognitive prostheses: AI systems that extend our memory, sharpen our reasoning, enhance our decision-making, and accelerate many of our work tasks. In other words, if superintelligence is coming, we should ensure it’s ours too—not just something we watch from the outside. This isn’t just a vision of empowerment—it may be a survival strategy.

If we do have superhuman AI by 2027, one of the first transformative things it could help us do is solve the last mile of cognitive integration: how to safely and effectively get information directly into the brain. Current brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies can read simple intent signals or restore lost sensory input—but they don’t yet allow full high-bandwidth input into the mind. That could change rapidly if AI joins the research effort. The most profound use of AI may not be replacing us—but wiring it into us, upgrading human cognition to remain sovereign and empowered in an age of accelerating intelligence.

If augmentation is about extending our abilities through external tools, integration is about removing the boundary altogether.

We’re already seeing the first glimmers of this reality. Companies like Neuralink, Synchron, and academic labs around the world are experimenting with BCIs—devices that allow neural signals to be read, interpreted, and even written to in real time. The early applications are medical: helping people with paralysis move robotic limbs, allowing those with ALS to communicate using thought alone, or restoring partial vision through neuro-stimulation.

But the implications go far beyond medicine. Imagine thinking a question and receiving the answer not as a written or spoken response, but as an instant knowing—an AI completing your thought. Imagine recalling complex information—formulas, histories, languages—without memorization. Imagine communicating brain-to-brain, bypassing language altogether.

This isn’t science fiction anymore. It’s a rapidly accelerating frontier.

But it’s also one that demands deeper reflection. Because as soon as we allow AI to speak within our minds—not just to them—we open the door to new possibilities… and profound risks.

Automation that once seemed unthinkable

We’ve seen this pattern before: when automation first replaces a manual process, there’s often resistance—until the new way becomes second nature. Drivers once prized manual transmissions for the control they offered, but today automatic transmissions are the norm. Elevators once required operators; now we step in, press a button, and trust the system. Pilots rely heavily on autopilot systems for most of a flight. I used to insist on driving myself, but now I regularly let my Tesla navigate and drive me where I need to go—more safely and efficiently than I might have done on my own. Paper maps have given way to GPS directions we follow almost without question. In each of these shifts, what began as optional assistance quietly became the default.

Prosthetics that surpass the original

We’ve also seen how physical augmentation has moved from restoration to enhancement. Cochlear implants now allow some deaf individuals to hear. Pacemakers and insulin pumps regulate vital bodily functions without conscious effort. And prosthetic limbs—once designed merely to restore basic mobility—have evolved so far that some athletes with advanced prosthetic legs can now outrun competitors with natural limbs. What began as a tool to bridge a deficit has, in some cases, surpassed the original. That’s the trajectory AI may be on as a cognitive prosthesis—not just restoring lost capability or offering convenience, but potentially enhancing the human mind itself beyond its natural limits.

Guidance for the AI Integration Journey

1. Augment: Enhance Productivity and Clarity

Before AI moves into our minds, we must become adept at using it as a cognitive partner—to summarize complex texts, generate ideas, extend our creativity, and organize our time more intelligently.

Guidance: Use AI tools not to shortcut thinking, but to refine it. Let it elevate your work, not define it. Keep authorship and agency in your hands. The recent MIT brain imaging study reinforced the need for humans to remain in control, have agency, and only use the AI to augment human activity. Not doing so, deactivates brain activity in key areas and potentially leads them to atrophy.

2. Elevate: Cultivate What AI Can’t Replace

As AI takes on more tasks, we must double down on what makes us uniquely human: emotional intelligence, ethical reasoning, embodied presence, deep empathy, the capacity for moral imagination, and the ability to live and engage in the physical world.

Guidance: Invest in reflective practices, interpersonal connection, and community. AI doesn’t feel, believe, or belong, we do. And AI doesn’t live in the physical world, we do.

3. Integrate: Consider Direct Neural Interfaces Carefully

When we move toward physically integrating AI into the brain, the goal isn’t to surrender control. It’s to enable real-time, high-bandwidth interaction—unlocking new frontiers of creativity, memory, and decision-making.

Guidance: Treat neural-AI integration like a sacred trust. Require transparency, revocability, and strict governance. Ensure the ability to turn off the AI connection directly the moment we want to.

The Caution: Who Do We Trust with Our Minds?

As AI technologies inch closer to our neural core, we must examine not only what’s possible—but who controls it.

Many of the most advanced companies in AI and neural interface development are led by individuals whose worldviews aren’t necessarily the same as ours nor focused on the requisite cautions and they’re often laser focused on simply maximizing profit. They often have with little regard for collective ethics, transparency, or equity.

When Neuralink arranges human trials, who decides what’s tested—and what’s discarded?

When OpenAI’s governance shifts quietly, or powerful models are trained in secret, what safeguards protect democratic access?

When startups partner with authoritarian regimes or military contractors, what gets compromised?

Guidance: We need to advocate for democratized AI governance. Push for international AI ethics charters, public oversight, and independent regulation. If we entrust our cognition to systems, those systems must be accountable.

The Shadow Side: Mass Job Displacement

These advancements aren’t just philosophical—they’re economic.

Generative AI and robotic process automation are poised to displace tens—perhaps hundreds—of millions of jobs worldwide over the next decade.

Up to 30% of current jobs are at risk of full or partial automation by 2030 (McKinsey) and many more recent estimates from tech CEOs makes that percentage even higher and sooner.

How will the tax revenue that’s lost when workers are replaced by AI be made up? Should we have an AI tax that can be used to pay the many workers who will no longer have jobs?

Guidance: Prepare yourself and others not just to adapt, but to shape the post-AI economy. Focus on roles where humanness is central: teaching, care, ethics, interpretation, strategy. We need to advocate for economic safety nets.

Where We’Re Headed—And What We Must Choose

The future may not arrive all at once, but in subtle layers:

First, more seamless interfaces. Then cognitive co-pilots. Then, slowly, systems that aren’t just responding to us—but collaborating with us.

And eventually, systems that are so deeply integrated into our minds that the boundary between thought and computation disappears.

Some will resist this path—defending the purity of the un-augmented human mind. Others will embrace it fully, seeking transcendence through merging with machines. Most of us will likely live in the tension between those poles.

For me, this isn’t about becoming less human. It’s about exploring what else it means to be human in a time of accelerating intelligence—both biological and artificial.

I began this journey by studying how the body speaks beneath the surface—how physiological signals could reveal truths people couldn’t always articulate. That early work taught me that intelligence isn’t only what we say, but how we feel, how we respond, how we adapt.

Now, I find myself wondering: What happens when that responsiveness is shared—not just with other humans, but with systems that can learn us, know us, perhaps even shape us?

The Questions We Must Ask

Where does thought end and influence begin?

If an AI completes your sentence or suggests an emotional response, how do you know which part was “you”?

Who controls the update?

If a neural implant can be improved over time, who governs what gets “patched” into your consciousness?

What happens to privacy—when your thoughts are no longer entirely your own?

When brain data is digitized, what’s protected? What’s monetized?

Do we lose something fundamentally human?

Or are we simply evolving into a new form of human—one where identity includes not only memory and biology, but algorithms and code?

This is the threshold we’re approaching. And the decision isn’t just technical—it’s ethical, psychological, even spiritual.

An Invitation

This post is not a manifesto. It’s a question, a personal question. Or perhaps many questions, some of which are as follows.

What kind of relationship do you want with AI?

How far would you go to enhance your capabilities, your memory, your insight?

And where would you draw the line?

Would you welcome AI into your mind—if it could help you think more clearly, remember more deeply, act more wisely?

Or does something in you pull back at that edge?

Let’s explore that frontier—together.

Top 10 UX Research Impact Best Practices

I recently joined the advisory board of Food for Climate League, a remarkable nonprofit dedicated to making climate-smart eating the norm. The organization has a talented and passionate team of researchers, designers, and project managers committed to driving meaningful change. I was honored to be invited to lead an educational session for the team on a topic close to my heart: “Making Research the Foundation for Organizational Impact.”

During the session, I shared a set of best practices that I’ve found to be essential in having impact with research in the work I’ve done with numerous large companies, startups, and nonprofits. I promised the team I’d follow up with a written version, and I’m sharing it here in the hope that others might benefit as well.

So here’s my top 10 list:

Focus on the outcome first—not the study. Many researchers get too caught up in the details of the study they’re designing when they should first think about the intended impact that they could have with the research and then design the study accordingly. This may require a rethinking the question being asked to take a broader perspective.

When your study is complete—you're only half done. The organization that hired you didn’t do so just to have you carry out studies. They hired you to use your research craft to have impact in order to make the organization more successful. So having completed a study doesn’t accomplish that—making sure that the insights from the study have impact on the organization’s deliverables does.

A higher response rate is better than more questions asked. When doing a survey, there is an inverse relation between the number of questions you ask and the response rate you’ll get. The more questions you ask, the fewer responses you’ll get. And that lower response rate means that you’re not getting a representative sampling of the target population.

If impact is your focus—one question may be preferable to many. It’s better to ask a single question that’s directly related to impact in a survey and then to follow up with some additional interviewing to further explore the additional questions you have. In fact, a simple unambiguous survey question is often the best way to get a representative high response rate while interviews are typically the preferred method of getting richer and more meaningful substantive information.

Plan your data analysis strategy before starting the study. Researchers, and even more often non-researchers doing research, will design and carry out the study and then think about how to analyze the data. Especially if you’re looking to have maximum impact from your research, you should plan your data analysis approach before you conduct the study. That approach will typically better inform the design of the study for organizational impact.

Run at the speed of the team—don't be a consultant that flies in. Researchers often get the requirements for a study, then carry out the study on their own, and then present the results to the team that requested the study. That approach runs the risk of the requirements having changed over time. A much better approach to ensure that your research has impact is to stay connected with the team requesting the research so that you can make necessary changes as requirements change. It may lead you to decide to use a different more time efficient research method or one that better addresses the needs of the team given where they are in the project.

Stay aligned with the team—get them involved in your study. Another reason to work closely with the rest of the team and even have them be present during some of the carrying out of the study is that it will ensure that everyone on the team better understands the insights from the research because they will have witnessed some of the research that led to them.

Accelerate your research with the effective use of AI. An additional way to ensure that your research has impact is to make the carrying out of it more efficient, effective, and timely. You can do that with the effective use of AI.

Empathize with the recipients/audience. Even though researchers champion empathizing with the users when conducting research for the design of a product or service, they often forget to do so when creating the product of their own work—the presentation of their research results. The recipients/audience are interested in the information that will have impact for their organization’s success so don’t start by presenting all the geeky sampling, methods, and data analysis details. Get to the point quickly regarding information that is most relevant to providing the insights for the organization. If there are question about methodology, you can have those in some backup slides.

You should be running a research program—not just individual studies. To have maximum impact, your research studies should form part of a larger research program. The studies should build upon each other and the research program as a whole should provide insight beyond the insights from individual point research studies.

While these are not exhaustive, I hope these best practices from my experience will help you to further hone your research practice.

Believe in People Again: Human Nature isn’t Evil

I lament the state of the world like I assume most of you do. It’s truly heartbreaking to read—and even more so to watch—the news. It might leave you to conclude that human nature itself is awful and even evil. But nothing could be further from the truth says Rutger Bregman in his amazingly hopeful book Humankind.

BREGMAN’S THESIS

Bregman’s central thesis is simple, but would be perceived as radical in today’s world: that people are, at their core, decent. They’re not perfect—but they’re kind, cooperative, and naturally seek social connection. But almost every institution we interact with operates on the opposite belief: that humans are essentially selfish, lazy, and in need of constant control.

TODAY’S WORLDVIEW

And that pervasive belief provides a distorted lens though which society is viewed and views itself.

In the corporate world, it results in toxic management practices, dehumanizing performance metrics, mass layoffs justified as “strategic,” and a relentless pursuit of shareholder value at the expense of workers, communities, and the planet. Employees are often treated not as trusted team members, but as potential unmotivated workers who must be surveilled, micromanaged, or automated out of existence.

We need look no further than the current U.S. political environment. The prevailing style of governance feeds on fear—of others, of institutions, even of democracy itself. It thrives on division, suspicion, and distrust. If people are assumed to be self-interested and dangerous, then democracy becomes a liability—and authoritarianism becomes justifiable. This narrative fuels crackdowns on protest, vilification of immigrants, and deliberate disinformation campaigns.

But this isn’t just an American problem. Around the world, similar dynamics are playing out—from nationalist movements in Europe to autocratic crackdowns in parts of Asia and South America. In each case, leaders exploit the idea that humans are inherently selfish and untrustworthy to justify centralizing power, dismantling protections for civil society, and scapegoating vulnerable groups. It’s a worldview that excuses control instead of inviting cooperation—and I believe it has enabled the rise of several of today’s political figures who are actively undermining both people and the planet.

BREGMAN’S REANALYSIS

But here’s where Humankind is most powerful: Bregman take a critical deep look into the seminal studies and media coverage of world events that gave us this negative view of humanity.

SEMINAL PSYCHOLOGY STUDIES

He takes aim at the very studies that shaped our understanding of human nature, including some of psychology’s most famous experiments. He reveals how the Stanford Prison Experiment and Milgram’s obedience studies—often cited as proof of humanity’s cruelty and blind conformity—were fundamentally flawed. Both ignored contradictory findings, used manipulated or coerced conditions, and were shaped by experimenters who encouraged the very behaviors they claimed to “discover.” These weren’t neutral insights into human nature; they were contrived dramas that made for great headlines and career boosts—but terrible science.

I find it deeply disturbing that psychologists like Philip Zimbardo and Stanley Milgram gained fame by promoting these narratives. Their studies didn’t simply reflect a misunderstanding of people—they actively shaped it. Millions have since accepted the idea that we are inherently cruel or corruptible, because the science said so. But as Bregman shows, the real science says otherwise.

DISASTER MYTHS

He also dismantles widespread myths about human behavior during disasters—the assumption that people panic, loot, or turn on each other when things fall apart. He shares example after example—from the London Blitz to Hurricane Katrina to the aftermath of 9/11—where people didn’t descend into chaos. Instead, they rose to the occasion. They formed mutual aid groups, shared food and shelter, helped strangers, and built community. Yet the media coverage and government responses often fixate on fear and control. Policymakers prepare for the worst in people instead of trusting the best. Bregman argues that this has real consequences: when you assume people are dangerous, you treat them as such—and they begin to believe it themselves.

THE REALITY IN WAR

Bregman also brings attention to the realities of warfare that challenge the assumption of innate human violence. Historically, studies have shown that many soldiers, when placed in combat situations, go to great lengths to avoid killing—even when directly ordered to do so. In both World Wars, a significant percentage of soldiers intentionally fired above the enemy or found ways to avoid pulling the trigger, such as loudly reloading their rifles without actually engaging. This reluctance to kill underscores a profound psychological and moral barrier: when people encounter others face-to-face, empathy often overrides aggression. But this dynamic begins to break down with distance and dehumanization. Military leaders issuing commands from afar, or drone operators detached from the human consequences of their actions, are far more likely to carry out or order lethal violence. The greater the distance—physically, psychologically, or institutionally—the easier it becomes to suppress our innate aversion to harm.

ACTION AND CONSEQUENCE MORAL DISTANCE

In addition to the experiences in war, Bregman also draws attention to other modern systems that obscure responsibility and erode empathy by creating moral distance between action and consequence. Nowhere is this clearer than in the world of industrial animal agriculture. While many consumers are shielded from the violence required to produce their food, slaughterhouse workers bear the psychological burden. Studies have shown that these workers often suffer from symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress—what some researchers call Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS)—because their jobs force them to suppress innate human compassion in order to carry out repeated acts of killing. This moral dissonance isn’t just harmful to the animals; it deeply wounds the people involved as well. Bregman argues that when systems demand the suppression of our better instincts, it’s not a reflection of human nature—it’s a distortion of it. In a world that often incentivizes detachment and dehumanization, he urges us to recognize the cost and to reimagine systems that are aligned with empathy, not in conflict with it.

BYSTANDER APATHY

One of the most enduring stories used to support the idea that people are indifferent or apathetic is the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City. For decades, it was cited in psychology textbooks as a prime example of the “bystander effect”—the claim that 38 witnesses saw or heard the attack and did nothing. But Bregman revisits more recent investigations that reveal this narrative was largely false. Many of the supposed witnesses didn’t realize what was happening, several did intervene or call the police, and one even held Genovese in her final moments. The original story, sensationalized by the media and amplified by academics, served to reinforce the belief that people turn a blind eye to others in distress. In truth, the case illustrates how misleading reporting and oversimplified theories can shape our view of human nature—and how that view can be profoundly wrong.

Rethinking How We Lead, Work, and Govern

It means we must rethink leadership—not as command and control, but as trust and service. We must design workplaces and communities that assume people want to contribute, not coast. We must build governments and institutions that share power rather than hoard it. And we must resist political movements built on fear, by insisting on a more compassionate, evidence-based view of who we really are.

Bregman reminds us that the future isn’t predetermined—it’s shaped by the stories we tell about ourselves. And right now, many of the stories we’ve accepted as “truth” are deeply misleading. If we want to create a better world, we need to start by changing the narrative. And even to simply change our worldview—to not focus as much on what evil leaders are doing but instead on the decency of everyone else. And to realize and try to foster direct interactions with one another rather than relying solely on technology-mediated ones (especially ones that are anonymous) that tend to dehumanize interactions.

So maybe the first step is this simple: Believe in people again.

Habits for a Better World: Built on Research, Powered by People, Designed for Impact

INITIAL INTENT

When filmmaker Carly Williams and I first met over a year ago, we quickly discovered a shared vision: to do our part in making the world better. We decided to join forces, combining our skills and experience—mine in research and design, hers in storytelling and filmmaking—to inspire individual behavior change that contributes to a better world.

Initially, we thought we’d simply make a documentary. That’s how most documentaries begin—with creators deciding what they believe the world needs to see. It’s also how most startups begin—with founders convinced they know what the world needs. But that top-down approach is often flawed. It’s why most documentaries fall flat and why more than 90% of startups fail.

We committed to doing things differently—grounding everything in UX research to deeply understand people, meeting them where they are, and then using design and storytelling to spark meaningful, lasting change.

CONDUCTING RESEARCH

More than 300 researchers, designers, and filmmakers from around the world shared our vision and joined us. They began by reviewing the relevant scientific literature to identify which individual behavior changes would most effectively address the global challenges they had chosen to focus on—such as climate change, human illness, biodiversity loss, animal and human suffering, ethical AI adoption, and more.

After a period of introspection to assess how closely their own behaviors aligned with the evidence, the teams conducted original research studies to understand how aligned others were with these findings—and to uncover the key barriers preventing broader adoption of the desired behaviors.

What they discovered was both revealing and pivotal: creating a documentary alone wasn’t the most effective way to reach people where they are, nor was it enough to support them on their journey toward change. This research directly shaped our design process—from ideation to storyboard—and led to a key insight: we needed to build an entire ecosystem. One that could not only inspire change in a variety of ways, but also offer support tailored to how people actually want to be supported.

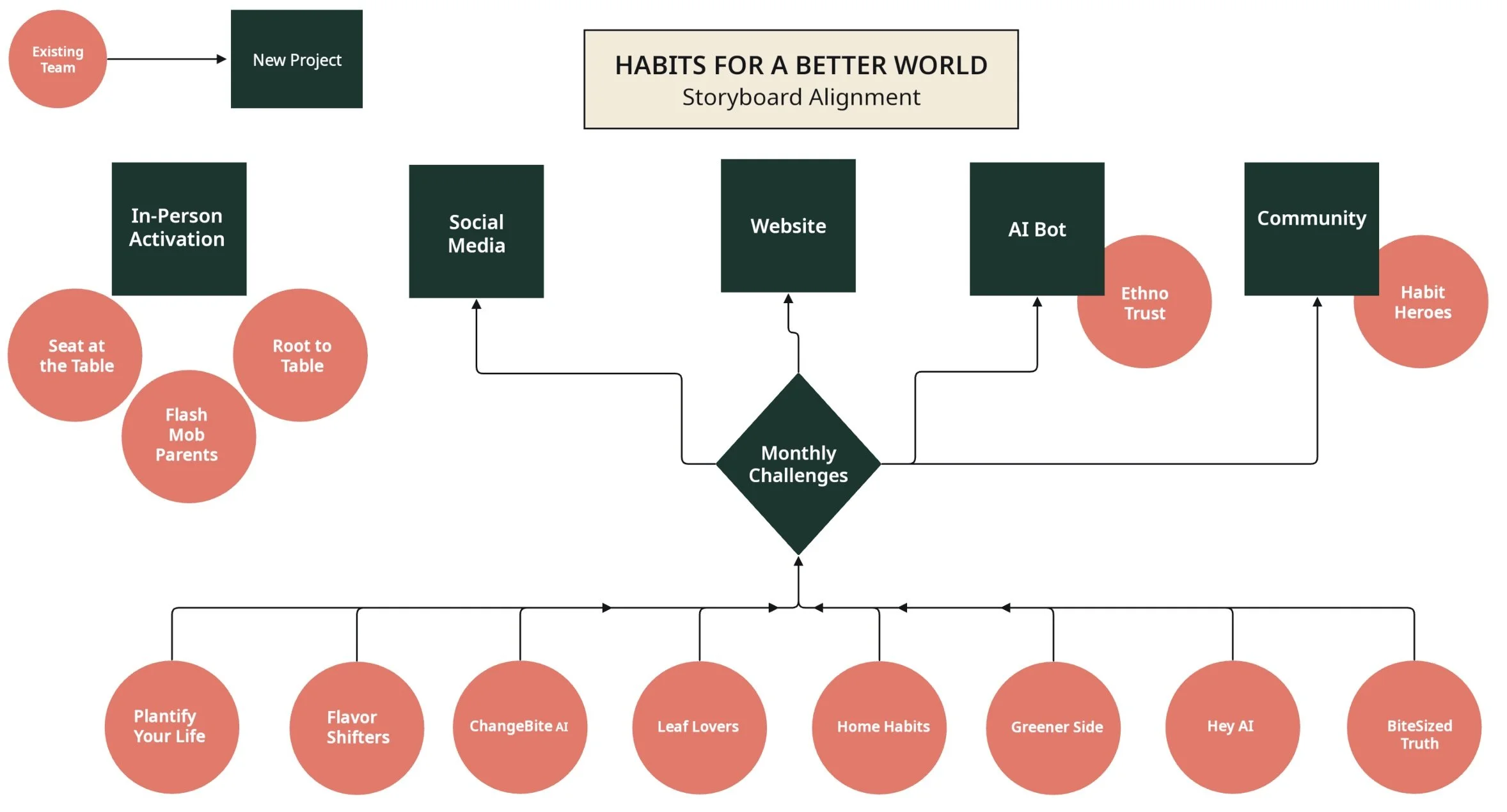

HBW ECOSYSTEM

As the illustration shows, our behavior-change ecosystem begins with social media campaigns designed to spark inspiration and awareness. But we also learned that digital outreach alone wasn’t enough. To truly meet people where they are, we needed to go beyond the screen—so we’re also planning in-person activations to bring these ideas to life more tangibly.

To support individuals on their change journey, we’re developing several key tools: a GenAI-powered bot built on a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) framework to answer questions using only trusted, curated information; a digital community platform for asynchronous peer-to-peer exchange; and monthly live Zoom meetups for real-time connection.

The AI bot’s implementation is guided by the recommendations developed by our AI research team—including energy-efficient processing, multimodal interaction (text and voice), and design safeguards to reduce the risk of digital dependency or “digital dementia.” Each element of this ecosystem is grounded in UX research and built to support behavior change in ways that are intelligent, ethical, and human-centered.

TEAM STRUCTURE AND FLOW

The storyboards that emerged from our research teams—while varied in content and focus—shared striking structural similarities. Most included both an inspirational trigger (such as a social media campaign or in-person activation) and a sustained support mechanism (such as an app or digital community) to help individuals maintain their behavior change. Recognizing that it would be impractical for each team to independently develop full-scale campaigns, platforms, or applications, Carly and I decided to form new cross-functional teams—shown in black squares on the visual—with specialized expertise in areas like social media campaigns, website development, AI bot design, and community platform implementation.

At the same time, we were deeply committed to honoring the cohesion and momentum of the original project teams—shown in red circles—based on strong feedback from participants who wanted to remain intact. Two of those teams, in fact, will be directly collaborating with the new specialist groups: the EthnoTrust team, which focused on AI best practices, is now working with the AI bot team, while the Habit Heroes team, which proposed a digital community, is collaborating with the community implementation group.

The in-person activation teams are also joining forces to co-design reusable materials for events and workshops. Meanwhile, all remaining core teams along the bottom row of the visual will work alongside the new central teams. One team has also proposed a monthly challenge model to sequentially spotlight each major behavior-change theme. Under this model, each team will partner with the:

Social media team to co-create challenge-specific campaign content

Website team to ensure relevant materials are available online

AI bot team to integrate challenge-related trusted data into the assistant

Community team to provide moderators with topical expertise for digital forums and monthly meetups

This new structure enables us to scale efficiently while preserving the integrity and enthusiasm of the original teams—and ensures that each challenge we tackle benefits from deep research, cohesive storytelling, and sustained community support.

NEW ADDITIONAL SKILLS

Leading this organization continues to be an absolute delight—especially because people regularly reach out asking how they can get involved. In just the past few months, we’ve welcomed around 20 new members. To ensure everyone is meaningfully engaged, we asked both new and existing members to complete a discipline and skills survey. Based on the results, we’ve thoughtfully assigned team members to the new cross-functional teams. Some existing members are also generously contributing to both their original teams and one of the new ones.

The survey also helped us identify a few remaining gaps—critical roles we’re now actively looking to fill. We’ve posted these open volunteer opportunities on our website and are currently seeking:

A Social Media Manager

A Development Project Manager/Scrum Master

Several General Project Managers

Additional Visual Designers

A GenAI RAG Developer

If you or someone you know might be a fit, please check out the new Volunteer Openings page on our website for more details and application instructions. We’d love to hear from you.

HAVING IMPACT

Carly and I are incredibly excited to be entering this production phase alongside the amazing members of this organization. We’ve already witnessed meaningful behavior change among our teams—and now we’re building on that foundation to deliver impact on a much larger scale.

Our commitment to UX research remains at the core of everything we do. It grounds our decisions in real human needs, behaviors, and insights—ensuring that what we create isn’t just innovative, but truly impactful.

This project is also somewhat novel in its approach to research. While many organizations have research teams, it’s unfortunately common for their insights to be overlooked or only selectively applied. As a result, too many leaders miss the opportunity to fully realize the impact they could achieve. From Day One, Carly and I made a different choice. We committed to letting the research lead—and we’ve stuck to that promise.

Initially, we believed our primary output would be a documentary. But the research told us otherwise. It showed us the need for a broader ecosystem of support and inspiration—across digital and in-person experiences. That’s what we’re building, and that’s what we’ll now bring to life.

We’re also excited to document this journey—showing how these teams turned research into action, and how that action leads to measurable behavior change that helps create a better world. That story will be told in the documentary we eventually produce—not as a starting point, but as a reflection of the real-world impact we’ll have achieved together.

To everyone who’s helped us get to this point—thank you. Carly and I are deeply grateful. And we’re energized and honored to continue this journey with all of you as we work together to deliver real impact, at scale, for a better world.

Grateful at 70: Thanks to the People Who Shaped My Journey So Far

I’ve rarely spoken about my age during my career. For decades, I worked alongside designers and researchers often half my age, and still do. Even my side projects tend to involve younger collaborators. I love that dynamic—and I think it’s one of the reasons I maintain a fresh, youthful perspective on life, staying curious, optimistic, and energized.

Now that I’ve retired—and there’s no hiding that I’m old enough to have done so—I’ve decided to be more open. I’m turning 70 this Saturday, May 24.

I’m deeply grateful to have reached this milestone. My father had his first heart attack at 51 and passed away a decade later. I credit my health today, in part, to living fully plant-based—but also to a life of meaning, learning, and purpose.

Through keynotes, classes, coaching, and our work at Habits for a Better World, I’ve realized how much I’ve learned over these seven decades—not just from the things I’ve done, but even more from the incredible people I’ve been lucky enough to work and live alongside.

This post is a heartfelt expression of gratitude. I’ve learned so much from so many. I can’t name everyone (that would take several books), but I hope some of those who’ve helped shape this life of mine will recognize themselves here. Please know that even if I don’t mention you directly, I carry your impact with me.

Thanks for being part of the journey so far. Here’s to learning, growing, and giving—at every age.

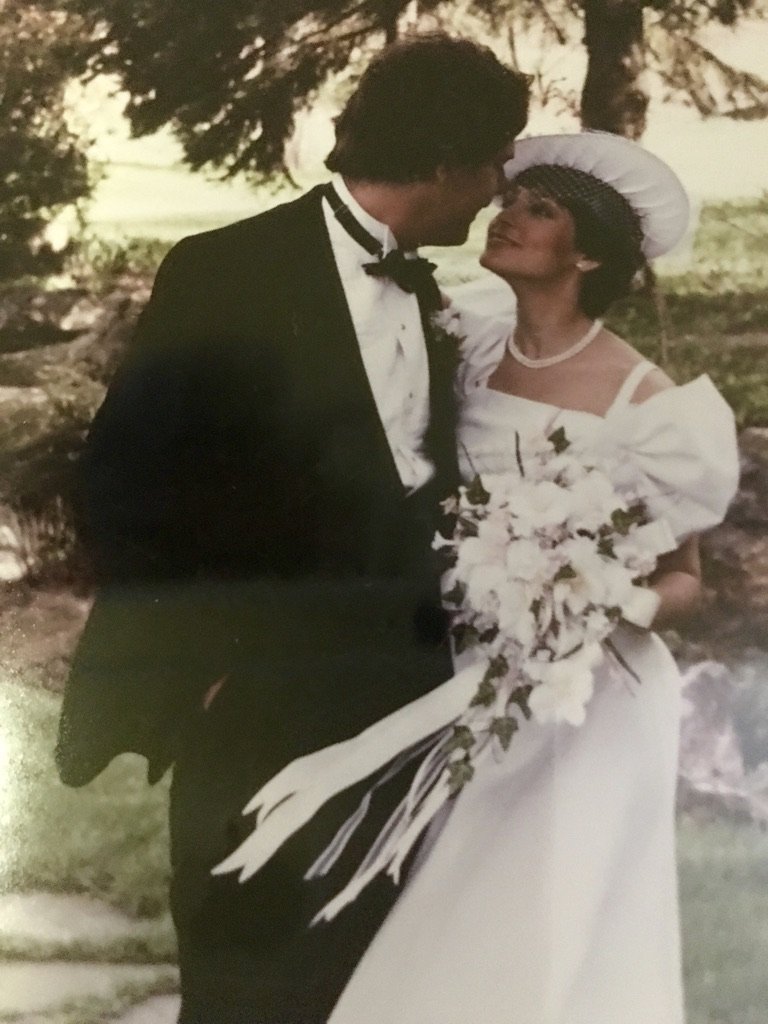

Top Row—my mother Gerritdina Leida Vredenburg, my brother Harrie Vredenburg and me, in elementary school, on a hockey team, playing Jesus in the musical Godspell, by brother and I signing together in our group Subway, playing guitar with the late Dario Ucheck, Second Row—getting married, my long-time Guys Afternoon Out friends, with Phil Gilbert, presenting a keynote, with Don Norman, Third Row—my former Austin IBM team, my former Toronto IBM Studio team, our Toronto-based extended family, my brother’s family, Bottom Row—my son and his partner, my kids, friend Paige Heron, friend Antonella Mintegui, my former IBM Head of Events Renee Albert and Chief of Staff Lauren Swanson, and Carly Williams, the co-founder with me of Habits for a Better World.

The Foundation—Early Life

Gerritdina Leida Vredenburg

My mother, Gerritdina Leida Vredenburg, had an outsized influence on my life. So much so that when she passed away, I recorded a special episode of my Life Habits Podcast to honor her memory and share the seven major lessons she taught me—lessons that continue to guide me to this day. Check out the podcast episode for those lessons.

My brother, Harrie Vredenburg, has been—and still is—among my closest friends. When we first arrived in Canada, it felt like the two of us against the world, navigating a new country and its unfamiliar ways. Over the years, we’ve been academic collaborators, confidants, and steady presences in each other’s lives. Check out his LinkedIn profile for more about him.

Brother Harrie and me in The Netherlands

One of the most important lessons we’ve learned is to recognize and accept how different we are in many ways—and how that honest acknowledgment has only deepened our bond. Because of the trauma I experienced during our immigration, I remember very little from the first ten years of my life and feel almost no connection to the country where I was born. But Harrie remembers, and now regularly shares stories from those early years—championing our connection to the Netherlands and helping me reclaim a part of our shared history.

Johannes Albertus Vredenburg

My father, Johannes Albertus Vredenburg, was a man of few words. From him, I learned the value of hard work—and the wisdom of knowing when to stay quiet in an interaction. He also inspired my lifelong love of music, especially classical and choral, through the sounds that filled our gezellige back room in the Netherlands, where he would sit reading the newspaper and smoking a cigar while music played softly in the background. Interestingly, this is an experience I do recall and it’s likely due to it’s emotional impact on me.

I’m particularly proud of his work as part of the resistance during the war—fighting to rid the world of fascism, hatred, and evil. He disliked boasting and spoke of it only rarely, but his quiet courage left a lasting impression on me. His example continues to inspire me to stand up against the fascism, hate, and injustice that persist in the world today.

When he caught me secretly smoking as a teenager, he didn’t scold or shame me. Instead, he quietly led by example. A heavy smoker of hand-rolled, unfiltered cigarettes, he put them down that day and never picked them up again. That single act of quiet integrity stayed with me. It inspired me to stop smoking too—and I never went back.

His example shaped more than just that one decision. It taught me the power of modeling over preaching—something I’ve tried to carry into many parts of my life, including my own role as a father.

I’m also deeply grateful for the experience of being an immigrant. As challenging as it was at times, it instilled in me a lasting empathy for anyone who is different—an empathy that has profoundly shaped how I engage with people and navigate the world. It’s one of the most formative and enduring gifts that experience gave me.

Leveling Up—School Years

When my family moved from the Netherlands to Canada, I struggled at first in school—not because of a learning disability, as some assumed, but because I didn’t yet speak English. It was my bow tie–wearing, older British gentleman of a teacher, Mr. McClean, who saw through my unwillingness to speak. He recognized the real issue and took it upon himself to teach me spoken and written English—quickly and effectively. I owe him a great deal. (Though I did later have to unlearn a few British pronunciations he passed along with the grammar.)

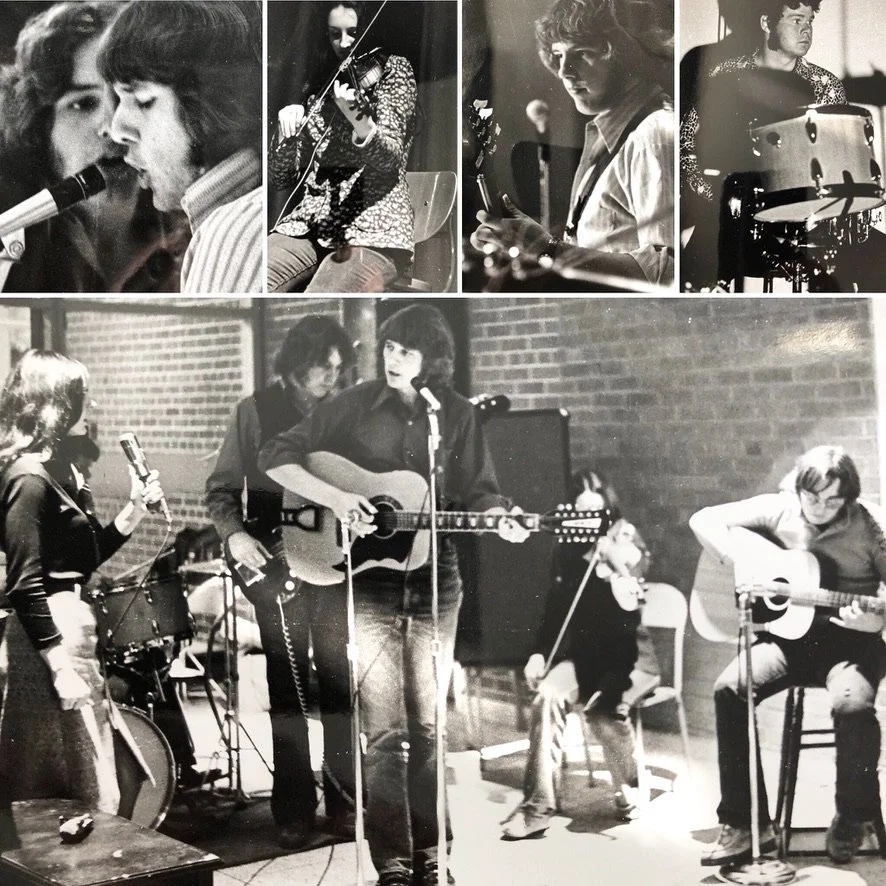

New City Singers Album

In high school, I founded a performance group called The New City Singers, and I loved every minute we spent performing together. But it was our teacher, Mr. Killey, who made something truly special possible. He helped me write a government Opportunities for Youth grant application—which, to our great excitement, was approved. That grant provided us with salaries, equipment, and even a van to tour across Ontario for a summer, performing for children’s camps, seniors’ homes, and the general public. That grant-writing experience served me well during subsequent stages of my life including securing a Medical Research Council Fellowship that paid for my graduate school studies.

Me playing some jazz trumpet

All through high school, I planned to pursue a career in music—specifically as a singer and performer. But my music teacher, Mr. Van Scherenberg, gently but firmly challenged that dream. He warned me that most people who earn a Bachelor of Music degree end up teaching music—and often find themselves listening to bad music all day. Although he was an exceptional teacher himself, I sensed that he may have had some regrets about the path he’d taken. His caution stuck with me. It was reinforced when I visited the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music and spoke with students there, a year before I needed to apply. They described spending most of their days alone in small practice rooms, and confirmed that performance-focused careers outside of teaching were extremely rare. That experience taught me a lesson I still apply today: before making a big decision, seek evidence, ask for honest advice, and look ahead to the likely reality—not just the ideal. I’ve subsequently learned to call that process foresighting, and it has guided me through many pivotal choices in life.

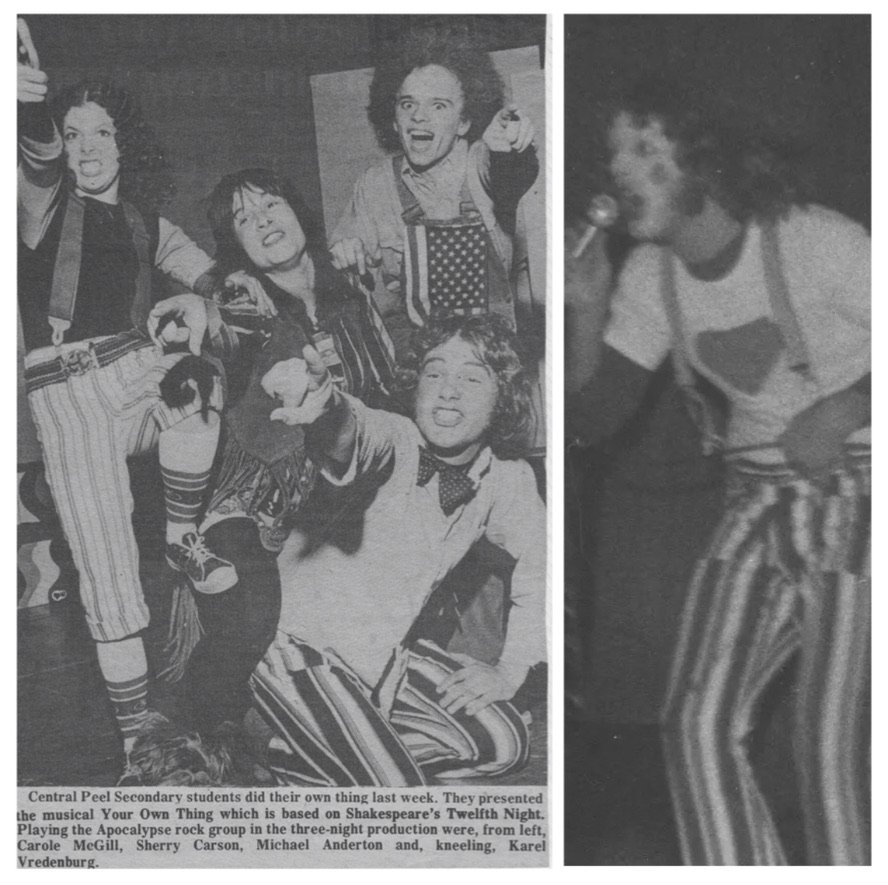

Me with my musical friends and me as Jesus in Godspell

Another teacher who had a profound impact on me was Val Grabove. Interestingly, I only ever referred to most of my teachers by their last names, but with Val, it was always her first name—that speaks to the connection she fostered. She was my high school theater arts teacher and the director of our plays and musicals. The lessons she taught me have stayed with me for life. Thanks to Val, I learned practical performance wisdom I still draw on every time I step on stage: don’t change anything major right before a performance, take a moment to scan and acclimate to the audience before walking out, and trust—truly trust—your fellow performers. I spent a lot of time performing in high school, whether at Music Nights or in musicals—including playing the lead role of Jesus in Godspell. I still cherish those experiences with fellow performers like Carol McGill, Sam Caruso, and Kevin Frank. That time in my life helped shape not only my voice but my confidence, presence, and sense of ensemble—all of which have carried into every stage I’ve stood on since.

The band Subway

My brother and I also had a band called Subway, where we mostly performed folk music. The band included some of our close friends—Libby Keenan, Dennis Johnson, Bryan Hammer, and Vanessa Hammer. While Harrie and I shared vocals, I also took on a new role at the time: playing bass guitar. It taught me how to contribute from the background—supporting the sound without being front and center—and I’ve carried that lesson into many aspects of my life since.

In addition to school performances, I also played in a professional house band every Saturday night. While it was a heady experience being a paid musician at that age, I quickly came to see some of the less glamorous sides of that life—like never being able to go out with my friends on performance nights or celebrate special occasions like New Year’s Eve. I also witnessed some of the grittier aspects of the business—for example, venues turning up the heat later in the evening to encourage more drinking and drive up alcohol sales. I learned the importance of having a plan to avoid drinking and driving, especially since band members were often given free drinks all night. I also picked up a trick for wrapping up a show that I’ve applied more broadly in life: when encore demands wouldn’t stop, I would close the night by singing the national anthem—a clear and respectful signal that the performance was truly over.

Dario and me

One member of that band, Dario Ucheck, left a lasting impression on me. Not only was he a gifted musician, but also an exceptional athlete. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he made the courageous decision to have his leg amputated where the tumor had developed. Determined to explore every possible path to healing, he sought out faith healers across the Northern United States—and I had the privilege of driving him to those visits. Watching Dario face his own mortality taught me more than I could have imagined. He began to savor life with extraordinary intensity—approaching each day and each experience with curiosity, humility, and gratitude. I remember how, when someone would request a song he didn’t know, he wouldn’t try to fake it—he’d simply say: “I don’t know that one—can you teach it to me?” That openness defined him. Whenever a new experience presented itself, he would engage with it fully—almost with a sense of reverence. Though cancer eventually took his life, his lessons have stayed with me and regularly provide me guidance.

Next Level Learning—University Years

As a first-year undergraduate, I would write out my assignments by hand and pay a fellow student to type them up—because I didn’t know how to type. The cost, along with the need to hand over papers a week in advance, motivated me to take a summer typing course at a community college beautifully situated on the shores of Lake Ontario.

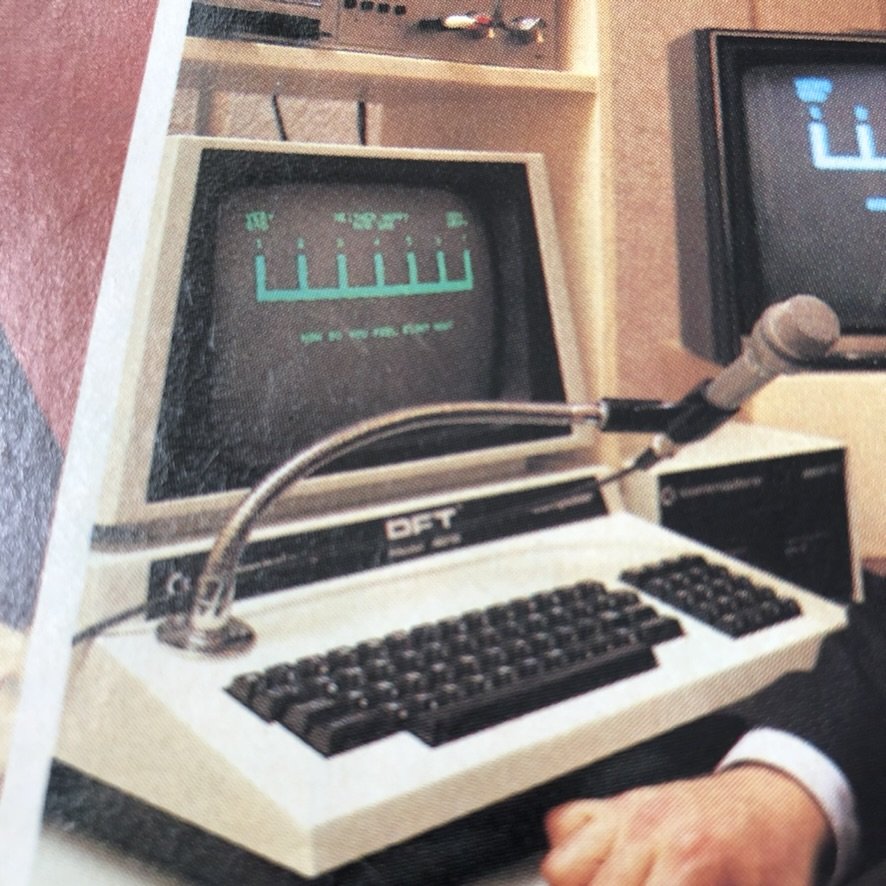

The typewriter I learned on except it didn’t have letters on the keys

I turned out to be the only man in the class. The women were mostly receptionists who, as I later learned, had been hired for their appearance and were now expected to learn a useful skill—how to type—this was, after all, 50 years ago. That environment pushed me to focus intensely on learning and improving, especially with weekly tests that publicly ranked each student’s typing speed and accuracy. I was proud (and a bit surprised) to be at the top of the class every week.

I’ve been thankful ever since. That one decision—to learn to type well—has paid off so well, especially now, when much of my work and creative life still flows through a keyboard.

A Commodore PET that I ran my experiments on in graduate school

My undergraduate and graduate student supervisor at the University of Toronto—where I pursued Cognitive Science and Clinical Psychology instead of music—was Professor Lester Krames. His lectures were always in high demand, thanks to his remarkable storytelling style. From him, I not only gained deep academic insights but also honed the storytelling skills I still use every day in teaching, keynotes, coaching, and design work.

I also had the privilege of serving as his Research Assistant, which included managing a human research lab at the university. That experience sparked my fascination with user experience research and design—ultimately shaping my entire career in those disciplines at IBM and beyond. Check out my blog post about that experience.

Erin and my wedding day

And it was in that very lab that I met Erin O’Brien, then an undergraduate student, who would later become my wife and life partner. We conducted research studies together, co-authored journal articles, drove to campus each day, and quickly became the best of friends, romantic partners, and ultimately, life partners. Erin has continued in the discipline and has served as an Editor for the American Psychological Association for many years. That chapter of my life marked not just the beginning of a profession—but the start of a profound personal journey as well.

The University of Toronto also connected me with others who would remain important throughout my life. One of them was Rick Hacket, a fellow undergraduate student at the time. Years later, we reconnected when I began teaching in the Executive MBA program at McMaster University—where he, too, was a faculty member.

Having Impact—Work & Change-making

Paul Smith

It was one of my friends from graduate school—Paul Smith—who I have to thank for initiating my career at IBM in research and design. During my doctoral work, I had completed eight additional studies beyond my dissertation, driven by a strong interest in exploring and mitigating gender differences in psychophysiological responses to computers. I developed a novel approach to user interface design, compared it to conventional designs, and found that my method performed significantly better.

I presented that research at a conference, which led not only to professional recognition but also to interviews in the press. Paul, who was then working at IBM, happened to hear one of those interviews and called me to ask, “Have you ever considered working for IBM?” I replied, “No, but I’m willing to consider it.”

That single conversation opened the door to what became a 36-year career at IBM. I’ve shared more about that journey in a previous post on this blog, but it all began with that unexpected call—from a friend who helped shift the course of my life.

I’d also like to call out a few colleagues and leaders I worked with over the years who left a lasting impression on me.

My first manager, Dave Pinkham, was a stickler for timeliness. I quickly adopted his approach, and throughout my career, my teams learned how important it was to be dependable and never keep others waiting.

Tony Temple, the VP under whom I led the transformation of User-Centered Design across IBM, taught me the importance of creating prototypes—of making ideas tangible early and often.

Bob Biamonte, another VP I reported to, wanted to promote me to Director of Design—only to discover that no such role existed at IBM at the time. That led to an important lesson in being resourceful: I worked with HR to help define and create the position myself.

Rod Smith, VP and IBM Fellow, offered one of the most enduring pieces of leadership advice I’ve received: don’t tell senior executives that the sky is falling—focus on the solution. That shift in mindset served me well throughout my executive career.

Phil Gilbert and me

Phil Gilbert, IBM’s General Manager of Design, had an outsized impact on me—and, in many ways, we influenced each other. His impact was so significant that I dedicated a blog post as a personal tribute to him. Check out that blog post here.

Katrina Alcorn and me

Katrina Alcorn, who succeeded Phil as General Manager of Design, was the best manager I ever had. She led with empathy, stayed closely connected, and empowered me in ways that deeply resonated. She also promoted me to Vice President, and I remain grateful for her belief in me and her leadership. I wrote a personal reflections blog post about Katrina and my team members previously.

Ana Manrique, Joan Haggarty, Sandra Tipton, Craig Moser, and Haidy Perez-Francis

Finally, my last manager at IBM, Justin Youngblood, supported my desire to conclude my long tenure with a six-month “farewell tour” of our design studios—giving me the chance to say goodbye in person and share lessons from my 36-year journey. I wrote a blog post detailing the lessons and advice I shared on that farewell tour and another sharing my career Q & A interview with Eleanor Bartosh.

I’d also like to give a shoutout to my Vice President of Design colleagues for supporting each other during some difficult times. We also had some great times together. I particularly appreciated the camaraderie and friendship. Thanks to Ana Manrique, Sandra Tipton, Craig Moser, and Haidy Perez-Francis. Also in the picture is dear colleague and friend Design Principal Joan Haggarty. And not in the picture, Shani Sandy, Joni Saylor, Robert Uthe, and Jeff Neely.

I’m also deeply grateful to the many talented managers and leaders who reported to me over the years—and to the 3,000 designers and 330 researchers I had the privilege of working alongside. It was an honor to be part of such a passionate, creative, and impactful community.

Teaching my EMBA class module

In addition to my work at IBM, about ten years ago I was approached by Len Waverman and Michael Hartmann, then Dean and Associate Dean of the DeGroote School of Business at McMaster University. They told me they had funding from Mr. DeGroote to develop a new educational program at the intersection of design, business, and healthcare—and asked if I would help develop and teach it. I agreed, and was appointed Industry Professor. That initial collaboration grew into an ongoing academic partnership, and I’ve especially valued continuing to work with Michael Hartmann on several adjacent programs and initiatives over the years.

Nicole Fich and Nital Jethalal together with the rest of the Board of Directors in a workshopping session

During the pandemic, I joined the Board of Directors of VegTO, where I served as Vice President alongside President Nital Jethalal and Treasurer Nicole Fich. Together, we led a significant transformation of the 75-year-old organization—rebranding it, overhauling key systems, and revitalizing the annual VegTO Fest. Both Nital and Nicole became and remain close friends, and I’m deeply grateful for the work we accomplished—and the bond we built—during such a challenging time.

Although I had previous board experience and teach innovation and creative problem solving at the Director’s College, it was my hands-on role co-leading the VegTO nonprofit that gave me the practical grounding and insight I now draw upon in co-leading my current nonprofit.

Don Norman and me

Another initiative that has had a major impact on me was co-founding the Future of Design Education Initiative with legendary design thinker Don Norman. Don, now in his 90s, taught me—by example—that you’re never too old to make a difference. He remains one of the most passionate, productive, and visionary people I know. His approach to retirement was an inspiration to me to not slow down but instead redirect my full-time focus toward purpose. That’s exactly what I’ve embraced. Check out the website describing our initiative and the resulting special issue journal with the curricular guidance. And Don and I have Meredith Davis for so expertly crafting that final deliverable.

Srini Srinivasan and Rebecca Breuer

At the beginning of the pandemic, I partnered with Srini Srinivasan, President of the World Design Organization, and Rebecca Breuer, Executive Director of Design for America, to launch the COVID-19 Design Challenge. Together with 225 volunteer designers and researchers, we mobilized quickly—and in just three weeks, we launched a major social media campaign to promote safe behaviors, along with several other impactful projects. Check out the website for more details.

I want to thank Srini, Rebecca, and every one of our incredible volunteers—not only for their contributions, but for helping to prove that when designers and researchers come together with purpose and urgency, we can create outsized impact using our skills and craft.

Carly Williams and me

After retiring from IBM, I teamed up with award-winning filmmaker Carly Williams to co-found and co-lead the nonprofit Habits for a Better World. Carly and I are kindred spirits and we share the leadership of our extraordinary global community of 300 volunteer researchers, designers, and filmmakers equally. This initiative and working with Carly has been, and continues to be, one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life. Carly is less than half of my age but she has taught me so much. We both also so appreciate the amazing volunteers who joined our nonprofit and who have done such great work. Thank you!

HUMAN CONNECTION—ENDURING FRIENDSHIP

Rick Sobiesiak, Scott Lewis, Mike Fischer, Paul Smith, and Bob Duchnicky